Day 12 – our last full weekday in South Africa – brought us to perhaps the most internationally well-known, and historical site in the country: Robben Island.

Located about seven miles from the Cape Town waterfront, Robben Island was used as a prison for almost three hundred years. The Dutch were the first to use this site, from as early as the 1600s. In fact, the name ‘Robben’ is Dutch for seal – a tribute to the many harbor seals that were once present on and around the island. In the mid 1800s, the British began using this site to house a growing leper population. More recently, Robben Island gained notice as the place where so many who fought against Apartheid were sent to serve their prison sentences. Nelson Mandela is perhaps the most famous of these, but thousands of political prisoners and freedom fighters were sentenced to this island prison. A site called South Africa History Online maintains a biographical profile of almost 1300 political prisoners held at Robben Island.

To tour Robben Island (or simply ‘the Island’), you purchase a ticket for a seat on one of four ferries that depart from Cape Town harbor. Tickets for adults cost 230 Rand (or $23) and tickets for those under 18 cost about $15. Passengers travel about 30 minutes by ferry to the prison, which is now a museum and UNESCO World Heritage site since the late 1990s.

Just a few notes on the ferry journey: First, if you plan to experience Robben Island, you should definitely book your tickets early. When we arrived at the ticket counter, a large sign alerted passengers that the next thirteen days’ passage was already completely sold out! Luckily for us, our always-prepared tour guide Brenna had booked our tickets months in advance, so we were all set. Second, a ticket for the ferry, which includes the tour of the prison, does not guarantee that the ferry will be running. High winds, rough seas, or inclement weather could cancel some or all of the scheduled ferry runs. You just have to time it right. In our case, it was a completely beautiful day, with little wind and light seas.

Once you board the ferry, you find your own seat, whether on deck or in an enclosed compartment. I chose a seat on the right that was outside and was lucky enough to catch a stunning view of Cape Town harbor, with the majestic backdrop of Table Mountain:

I felt the anticipation on deck, as most of the passengers were quietly staring ahead, waiting for their first glimpse of the Island. Before long, we were pulling into a sheltered dock area and disembarking onto the pier:

Once off the ferry, visitors walk a few yards to a parking area and board one of several tour buses. A visit to Robben Island is more than just a tour of the prison complex. It actually begins with a 30-minute tour bus drive around the grounds of the island, with a guide using a microphone to narrate the sights and providing historical information on the background of the Island. Our bus tour brought us to several interesting aspects of the island – completely separate from the actual prison compound. Here are four things that really stood out for me from the bus tour:

First, a graveyard still exists as evidence of the leper colony that was once housed here:

In addition, island officials decided that the lepers needed an official place to worship, so a church was built exclusively for them:

Second, at its highest point, there were as many as 1000 people living on the island (not counting prisoners or patients). These could be groundskeepers, guards, doctors, etc. Many brought their families, which included small children, to save on the long trip back and forth to the mainland. There was a need to educate these children, so a primary school was built in 1894. Our guide informed us that, with only 11 families currently residing on the island today, there is no longer any need for the school. This will be the first year since 1894 that the school will not be in operation.

Third, the island contained a limestone quarry, where maximum security prisoners were sent to do hard labor. Limestone was dug out of the quarry using tools, then broken up into gravel that was used in roads:

You may notice the hole in the back wall of the quarry. This is where tools and water were kept, but our guide told us that often prisoners would pause in there to discuss politics and news from the outside. Our guide also told us that quarry work was very dangerous, as no masks or protection were used. Prisoners often returned to their cells covered in white limestone dust, which got into their lungs and caused respiratory issues.

You may also notice that on the right side of the picture, in the foreground, there is a large pile of stones. This stone pile has historic significance, but after the fall of Apartheid. After Nelson Mandela was elected president of South Africa, almost 1000 former political prisoners attended a reunion on Robben Island. As the visitors toured the quarry, Nelson Mandela walked off to the side and dropped a rock onto the ground. This action was followed by many of the visitors, to form a type of cairn or rock memorial to their time on the Island:

My fourth item is the saddest of all, and concerns a political prisoner named Robert Sobukwe. Sobukwe was a very learned man, rising to university lecturer by 1954. He was one of the main voices who advocated for an African-only solution to Apartheid problems. His efforts led to a group of activists breaking away from the African National Congress and creating the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC), which Sobukwe was elected president of in 1959. In early 1960, Sobukwe organized a large demonstration against the white government’s requirement that all blacks carry pass books. Hundreds joined in the ‘anti-pass’ march. Along the way, Sobukwe and others were arrested and taken away. Sobukwe was charged with sedition and served a three-year prison term, but not on Robben Island. On May 3, 1963, one day before his sentence was to end, the white government passed the General Law Amendment Act. This law allowed the Justice Department to ‘detain’ political prisoners up to one additional year – and this detention could be done indefinitely. The Justice Department used this law to transfer Sobukwe to Robben Island and ‘detain’ him there for an additional SIX years. Government officials must have considered Sobukwe an extremely dangerous prisoner, for they had a separate structure built for him, away from the rest of the prisoners. In this ‘house’, he served the additional six years in solitary confinement:

Before the bus tour ended, we stopped at a small rest area for a brief break. As we got out of the bus to stretch, the view from this area was unbelievable, as you could clearly see all of Cape Town harbor and Table Mountain stretching out behind the city:

At the conclusion of the bus tour, we found ourselves back in the same parking lot by the ferry dock. We walked to the other end of the parking lot and entered the main prison complex. Ironically, the sign over the main gate read “We Serve With Pride”:

He explained that rooms like this were designed to hold 30 prisoners, but there were often 40-50 contained in this one room. Even though there are beds in the room now, prisoners slept on mats until 1978, when they were finally replaced by beds. You’ll see there are boxes mounted along the walls. These were places that prisoners stored their possessions. I was able to open one up to get a look inside – and they were NOT very big:

Our guide also explained that prisoners began in a group cell and, through good behavior, earned the right to move to a single cell and gain more privileges. If you were in a group cell, you were allowed to send and receive only ONE letter per month. You could also have a single visit per month. The “A” single cells gave prisoners the right to four letters and four visits per month. The “B” and “C” cells were for more serious prisoners, with inmates in the “B” cells receiving solitary confinement. Jama told us that on Robben Island, solitary required you to remain in your cell for 23 hours, with 30 minutes of exercise in the morning and 30 minutes of exercise in the afternoon.

We exited the group cell and made our way across the courtyard. Here, in the back corner, was an area known as “Mandela’s Garden”, where Nelson Mandela tended plants. It is well-known today because it was also a place that Mandela hid newspapers and other information that was smuggled into the prison!

This courtyard is very similar in size and layout to the one in which prisoners were forced to sit in the sun and break rocks mined from the quarry:

Off the courtyard, we proceeded to the different cell blocks, which were long corridors with cells on both sides. This corridor had two heavy metal doors at each end. When we entered, I noticed the doors had a large hole cut at eye-level. I assume this allowed the guards to lock down the corridor, but still keep watch on the prisoners:

This was the cell block that held Nelson Mandela for 18 years. His cell, the fourth on the right, was the only one with any materials in it, although the only ‘materials’ was a waste can, wooden stand, washing bowl and three mats:

The mood of the tour group got very quiet when we understood that this was Mandela’s cell. It’s odd to think that this tiny room could have any connection with Mandela, but I have to admit, there did seem to be a different feeling to it! I was surprised to learn that the cell was open and you were allowed to walk in. I did not, however, and just stayed on the outside, staring in from the corridor. I wondered how many times Mandela looked out through those bars, or out his window, and if he ever thought the day would come where he would ever be released. Even after 18 years, when he was moved from Robben Island to Pollsmoor Prison, it was another 9 years until his was finally released.

Mandela’s cell was a dramatic, but somber end to the prison tour. We were allowed to walk around the corridors, but most opted to head back to the dock area. I found myself off to the side, in the area where Jama was standing. I asked him if he wouldn’t mind telling me how he felt coming back to the place of his captivity for five years. He paused, but said “At first, it was very hard, but after a few months I got used to it.”

I had brought a copy of Voices of Robben Island, Jürgen Schadeberg’s excellent book that not only covers the history of the Island in detail, but has over 20 first-hand accounts from former prisoners:

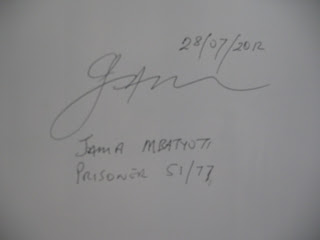

Although Jama was not directly featured in the book, his history was as much a part of the Island as anyone else’s. I asked him if he would mind signing my book and he agreed without any hesitation. His signature was just a scrawl, but it was what he wrote below the signature that made me stop: he wrote Prisoner 51/77, which was the Island’s system of labeling him as the 51st prisoner to be assigned to the prison in 1977. More than thirty years later, this man still identified himself with his prison number.

Located about seven miles from the Cape Town waterfront, Robben Island was used as a prison for almost three hundred years. The Dutch were the first to use this site, from as early as the 1600s. In fact, the name ‘Robben’ is Dutch for seal – a tribute to the many harbor seals that were once present on and around the island. In the mid 1800s, the British began using this site to house a growing leper population. More recently, Robben Island gained notice as the place where so many who fought against Apartheid were sent to serve their prison sentences. Nelson Mandela is perhaps the most famous of these, but thousands of political prisoners and freedom fighters were sentenced to this island prison. A site called South Africa History Online maintains a biographical profile of almost 1300 political prisoners held at Robben Island.

To tour Robben Island (or simply ‘the Island’), you purchase a ticket for a seat on one of four ferries that depart from Cape Town harbor. Tickets for adults cost 230 Rand (or $23) and tickets for those under 18 cost about $15. Passengers travel about 30 minutes by ferry to the prison, which is now a museum and UNESCO World Heritage site since the late 1990s.

Just a few notes on the ferry journey: First, if you plan to experience Robben Island, you should definitely book your tickets early. When we arrived at the ticket counter, a large sign alerted passengers that the next thirteen days’ passage was already completely sold out! Luckily for us, our always-prepared tour guide Brenna had booked our tickets months in advance, so we were all set. Second, a ticket for the ferry, which includes the tour of the prison, does not guarantee that the ferry will be running. High winds, rough seas, or inclement weather could cancel some or all of the scheduled ferry runs. You just have to time it right. In our case, it was a completely beautiful day, with little wind and light seas.

Once you board the ferry, you find your own seat, whether on deck or in an enclosed compartment. I chose a seat on the right that was outside and was lucky enough to catch a stunning view of Cape Town harbor, with the majestic backdrop of Table Mountain:

I felt the anticipation on deck, as most of the passengers were quietly staring ahead, waiting for their first glimpse of the Island. Before long, we were pulling into a sheltered dock area and disembarking onto the pier:

Once off the ferry, visitors walk a few yards to a parking area and board one of several tour buses. A visit to Robben Island is more than just a tour of the prison complex. It actually begins with a 30-minute tour bus drive around the grounds of the island, with a guide using a microphone to narrate the sights and providing historical information on the background of the Island. Our bus tour brought us to several interesting aspects of the island – completely separate from the actual prison compound. Here are four things that really stood out for me from the bus tour:

First, a graveyard still exists as evidence of the leper colony that was once housed here:

In addition, island officials decided that the lepers needed an official place to worship, so a church was built exclusively for them:

|

| (NOTE: No pews or benches were included!) |

Third, the island contained a limestone quarry, where maximum security prisoners were sent to do hard labor. Limestone was dug out of the quarry using tools, then broken up into gravel that was used in roads:

You may also notice that on the right side of the picture, in the foreground, there is a large pile of stones. This stone pile has historic significance, but after the fall of Apartheid. After Nelson Mandela was elected president of South Africa, almost 1000 former political prisoners attended a reunion on Robben Island. As the visitors toured the quarry, Nelson Mandela walked off to the side and dropped a rock onto the ground. This action was followed by many of the visitors, to form a type of cairn or rock memorial to their time on the Island:

My fourth item is the saddest of all, and concerns a political prisoner named Robert Sobukwe. Sobukwe was a very learned man, rising to university lecturer by 1954. He was one of the main voices who advocated for an African-only solution to Apartheid problems. His efforts led to a group of activists breaking away from the African National Congress and creating the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC), which Sobukwe was elected president of in 1959. In early 1960, Sobukwe organized a large demonstration against the white government’s requirement that all blacks carry pass books. Hundreds joined in the ‘anti-pass’ march. Along the way, Sobukwe and others were arrested and taken away. Sobukwe was charged with sedition and served a three-year prison term, but not on Robben Island. On May 3, 1963, one day before his sentence was to end, the white government passed the General Law Amendment Act. This law allowed the Justice Department to ‘detain’ political prisoners up to one additional year – and this detention could be done indefinitely. The Justice Department used this law to transfer Sobukwe to Robben Island and ‘detain’ him there for an additional SIX years. Government officials must have considered Sobukwe an extremely dangerous prisoner, for they had a separate structure built for him, away from the rest of the prisoners. In this ‘house’, he served the additional six years in solitary confinement:

|

| (I was too slow to get a good shot of Sobukwe’s prison house from the tour bus, so this image is borrowed from Tracks4Africa.co.za) |

At the conclusion of the bus tour, we found ourselves back in the same parking lot by the ferry dock. We walked to the other end of the parking lot and entered the main prison complex. Ironically, the sign over the main gate read “We Serve With Pride”:

As we passed through the gates, guides were standing in the entrance, collecting visitors into groups for their tour of the prison. It is very important to note that these guides were actually former prisoners who spent time on Robben Island! In my case, I got into a group that was guided by Jama Mbatyoti, who served five years (1977-1982) on Robben Island for participating in anti-Apartheid activities.

|

| Our guide: Jama Mbatyoti |

Jama led us into the main complex, where our first stop was the group prison cell:

He explained that rooms like this were designed to hold 30 prisoners, but there were often 40-50 contained in this one room. Even though there are beds in the room now, prisoners slept on mats until 1978, when they were finally replaced by beds. You’ll see there are boxes mounted along the walls. These were places that prisoners stored their possessions. I was able to open one up to get a look inside – and they were NOT very big:

Our guide also explained that prisoners began in a group cell and, through good behavior, earned the right to move to a single cell and gain more privileges. If you were in a group cell, you were allowed to send and receive only ONE letter per month. You could also have a single visit per month. The “A” single cells gave prisoners the right to four letters and four visits per month. The “B” and “C” cells were for more serious prisoners, with inmates in the “B” cells receiving solitary confinement. Jama told us that on Robben Island, solitary required you to remain in your cell for 23 hours, with 30 minutes of exercise in the morning and 30 minutes of exercise in the afternoon.

We exited the group cell and made our way across the courtyard. Here, in the back corner, was an area known as “Mandela’s Garden”, where Nelson Mandela tended plants. It is well-known today because it was also a place that Mandela hid newspapers and other information that was smuggled into the prison!

This courtyard is very similar in size and layout to the one in which prisoners were forced to sit in the sun and break rocks mined from the quarry:

|

| (Courtyard today) |

|

| (Similar area showing prisoners at hard labor) (Image from University of Minnesota) |

|

| Corridor of cells (Image borrowed from Flickr) |

|

| Steel doors at one end of the corridor |

|

| (Looking through a hole in the steel doors) |

|

| Inside of Nelson Mandela's cell |

Mandela’s cell was a dramatic, but somber end to the prison tour. We were allowed to walk around the corridors, but most opted to head back to the dock area. I found myself off to the side, in the area where Jama was standing. I asked him if he wouldn’t mind telling me how he felt coming back to the place of his captivity for five years. He paused, but said “At first, it was very hard, but after a few months I got used to it.”

I had brought a copy of Voices of Robben Island, Jürgen Schadeberg’s excellent book that not only covers the history of the Island in detail, but has over 20 first-hand accounts from former prisoners:

|

| Voices of Robben Island by Jürgen Schadeberg |